In the humanities, data mining necessarily entails an interdisciplinary and collaborative practice because it combines tools, techniques and methodologies from computer science and the humanities. As a consequence, data mining is often associated with the term digital humanities, which includes using cutting edge technology both to present the results of research and to conduct the research itself.

One of the resources we have used is the brilliant Old Bailey Online, which is “a fully searchable edition of the largest body of texts detailing the lives of non-elite people ever published, containing 197,745 criminal trials held at London’s central criminal court.” Not only can you perform detailed searches to bring back the full texts of the Proceedings (using keywords, time periods, surnames etc.), but you can also very easily tap into the database’s API, enabling you to do much more with the text than just read it. The API Demonstrator allows you to search the Proceedings in much the same way as the standard search, with some slight differences in the categories available.

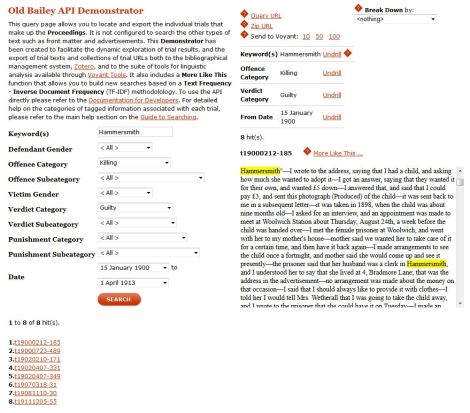

Where it really differs is the way that the results are then presented, and how you can modify, drill into, and extract them. To test it out for myself I decided to search for the Offence Category ‘Killing’, with a guilty verdict, between 1900 and 1913, and with the keyword Hammersmith (where I live). This produced a relatively small set of 8 results:

You are then given a range of options, for example the ability to ‘undrill’ search categories to reveal wider results. By undrilling ‘Hammersmith’ as a keyword I was able to quickly see that there were a total of 358 guilty verdicts for murder across the period selected, suggesting that as a percentage relatively few took place in or involved Hammersmith in some way. Of course no firm conclusions can be drawn from such basic analysis, but it demonstrates the kind of research questions that can be quickly assessed through tools such as this, such as which areas of London were most associated with certain types of crime in a certain period.

Another useful feature allows you to ‘break down’ your results into further categories that you may not have included in your original search, such as gender and punishment received. For my 8 results shown above, I was able to see that out of 9 defendants there were 8 males and 1 female, and out of 9 victims there were 6 males and 3 males, a potential source of interest for someone examining violence and gender relations. Again this shows how tools such as the Old Bailey API Demonstrator have really simplified and sped up the kind of analysis that would have previously taken much longer through reading alone.

As well as the features within the API, there are also options to export the texts to Zotero and Voyant Tools for further analysis. I discussed Voyant in my previous post so I won’t go into too much detail here, but it was interesting to see an API in action, allowing a mashup with another tool. As with many in the class I initially had trouble exporting my a from Old Bailey Online to Voyant, probably caused by too many people trying to use the service simultaneously, but when I tried later on with the results above I had no problem, and this was the result:

The ways you could then use Voyant to explore and analyse the texts would depend entirely on the type of research being carried out. If you were looking into the incidence of crime in a particular area, in this case Hammersmith, it would perhaps be useful to use the ‘keywords in context’ feature to quickly assess whether the killing actually took place there, or whether Hammersmith came up in the trial for another reason (i.e. movements of the accused, or origin of the victim). As previously discussed the word cloud could also be a useful trigger for further research, in this example the term ‘drink’, although relatively small, stood out and could be examined using the other tools to identify a potential relationship between alcohol and violence.

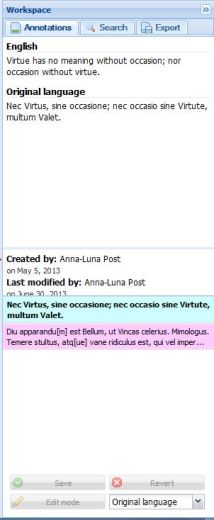

As well as Old Bailey Online we had the chance to look at some of the fascinating Text Mining projects being carried out by the Utrecht Univeristy Digital Humanities Lab, after a great talk by Ulrich Tiedau about his involvement with one of the projects. One that particularly caught my eye was Annotated Books Online (ABO), which aims to be “a digital library that reveals the variety of traces that readers left in their books.” In the context of DITA this made me think of a (perhaps tenuous) parallel with the way the web has advanced, moving from a rigid collection of documents (web 1.0) to a more interactive environment (web 2.0). In the case of books there is a long history of readers wanting to interact with the text on the page and add their own thoughts and thoeries – ABO is an attempt to collect examples of this and, through collaboration, enable its users to transcribe and translate the annotations:

This example is from a 1573 English edition of Machiavelli’s The Art of Warre, which was owned by Gabriel Harvey, and shows a translated transcription of a very poetic note on virtue. ABO differs from a resource such as Old Bailey Online as it is not presented as a completed tool, but as ‘a virtual research environment for scholars and students’, which will only be successful with thir collaboration and input. By working together on the existing collection, as well as adding to it, users of the resource will be able to build a very valuable set of texts which can then be mined and analysed by anyone interested in the subject.

Although there are certainly still some limitations with the tools discussed here, such as the initial difficulty of exporting the data and the inability to save work within Voyant, they are very impressive if you consider the fact that they are completely free to use and rely on the dedication and hardwork of the relatively few people behind them. Through my own limited experience I have seen how data mining, leading into some basic text analysis, can bring out many interesting issues and ideas for research. If these services, tools and technologies continue to advance and develop I think this can only be a good thing, as long as we remember to hold on to the accompanying close reading and qualitative analysis, arguably required to attain real meaning within the humanities.

Screenshots courtesy of http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/, http://voyant-tools.org/ and http://www.annotatedbooksonline.com/

Be interesting to consider whether studying marginalia and annotation will be ever harder in future when it is born digital?

LikeLike